.

At the meeting of the LRS on 13th May 2015 Alan Masson GM3PSP traced the history of motion picture sound tracks from the first sound-on-disc systems such as Vitaphone, used for The Jazz Singer in 1927 through analog sound-on-film systems including dye-only tracks, to the digital systems used latterly on film release prints.

A chemistry graduate, Alan spent his entire career with Kodak Motion Picture Division, working in the UK, Europe and the USA (Rochester NY and Hollywood CA). His background in Amateur Radio was very useful in a number of projects involving film sound tracks.

We shall be looking at all the formats used in film sound tracks, from the earliest sound-on-disc systems through to the digital formats used latterly.

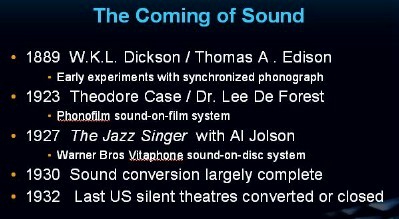

Sound was an objective for film systems from the earliest days. When the required technology became available in the late-1920s full conversion of the silent film industry to sound took just a few years.

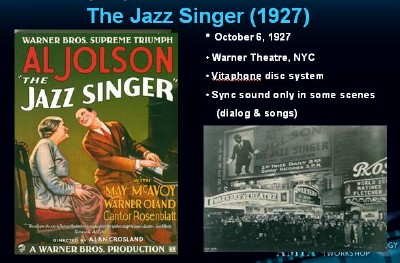

Although there had been some previous attempts at sound for movies, Warner Bros’ The Jazz Singer in 1927 marked the start of the serious conversion from silent- to sound movies.

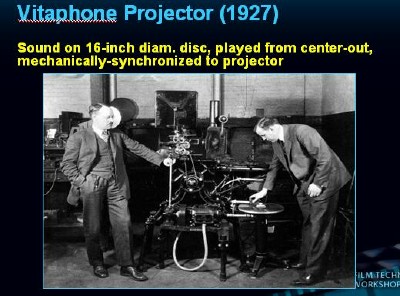

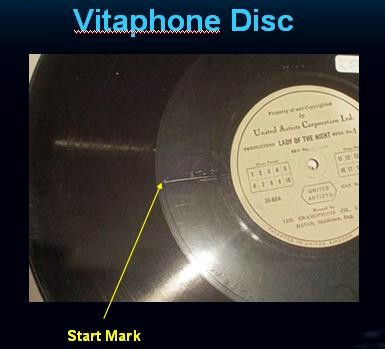

The Vitaphone projector, used for The Jazz Singer had a disc player mounted on the film projector and driven by a common shaft, making picture-sound synchronization reliable, provided they were started in sync and there were no scratches on the disc!

Synchronization (sync) of sound and picture was achieved by starting the film projector and the disc player at exactly the same time, using sync marks on the film and the disc, and the two players fed by a common drive.

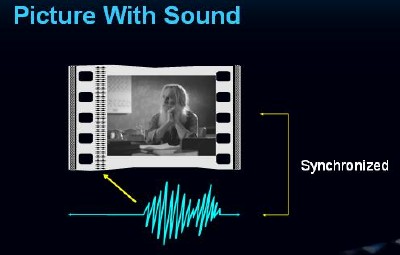

Maintaining sync with sound-on-disc systems was troublesome and it became apparent that the only 100% reliable way of achieving sync was to have both elements – picture and sound on the same medium – the film.

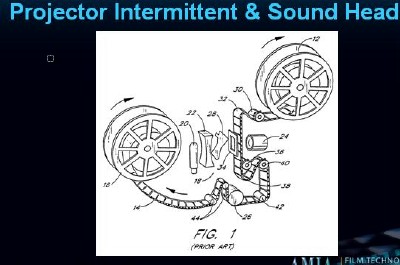

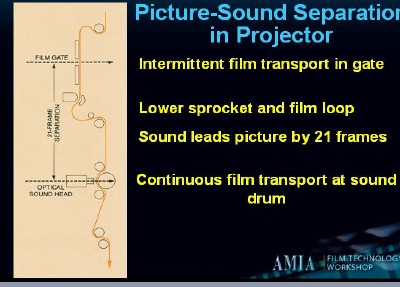

The only problem is that the film must move intermittently for the picture frames but continuously for the sound track. This is achieved by having the sound track separated by a fixed distance (21 frames ahead) from the corresponding picture frame.

In the projector the sound head is located below the picture gate, with a continuously-roatation sprocket driving the film, while the picture is pulled down intermittently with film loops above and below the gate.

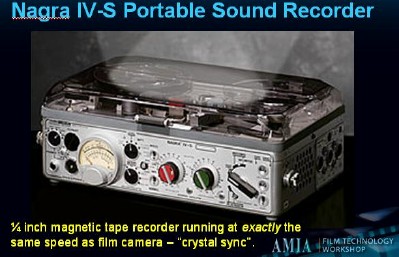

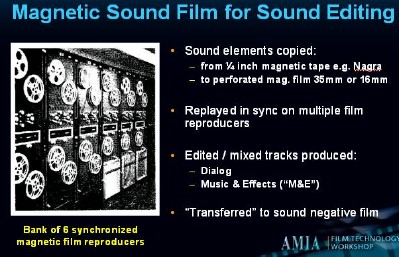

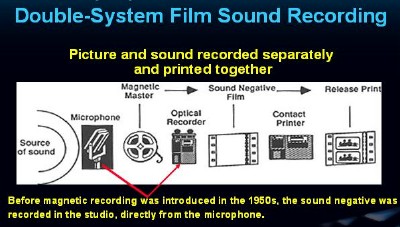

Getting back to the beginning of the sound track story, the track was typically recorded, quite separately from the picture, but in sync with it, by a 1/4 inch tape recorder such as a Nagra.

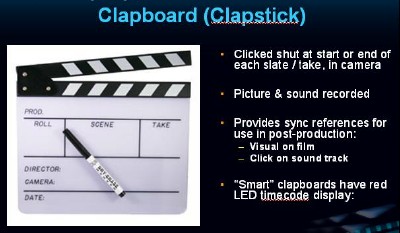

The clapboard was used at teh beginning (or end) or each “take” to provide visible and audible sync marks.

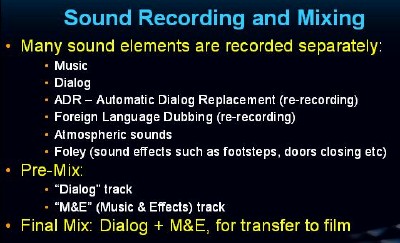

Many sound elements can be recorded separately and mixed together to give the final track. Usually two “Pre-Mix” elements are prepared – “Dialog” and “M&E” (Music & Effects) to allow different Dialog mixes for foreign language versions. The final sound mix is them recorded onto sound negative film.

For many years these Pre-Mixes were made using many 1/4 inch tape players slaved together in sync.

These are the principles of “Double-System” sound. Eventually the sound and picture are brought together when the sound negative film and picture negative film are printed together onto the Release Print film.

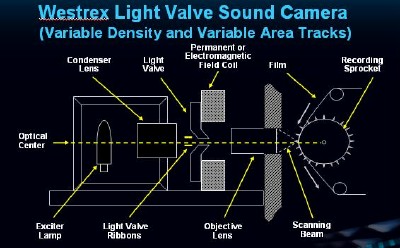

Different sound transfer cameras were used for early “variable-density” tracks and later “variable area” tracks.

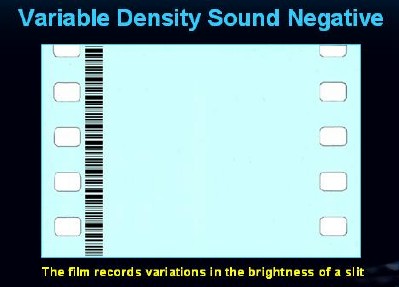

A variable density track is the image of a slit of light whose brightness is modulated by the sound signal from the Final Mix on tape. recorded onto the film.

One design is the light-valve canera where repulsion between two tiny metal ribbons, both carrying the sound signal in the same direction, modulates the width and therefore the brightness of a beam of light which is focussed onto the sound negative film.

By changing the orientation an optics, a variable-width slit of light is exposed onto the film. Thisis know as a “Variable Area” track.

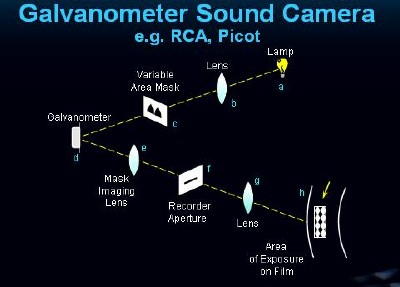

Another method of exposing a Variable-Area track is to use a tiny galvanometer movement (like an electrical meter) modulated by the sound signal. A mirror on the galvanometer roatates the reflected beam of one (or two) triangular beams of light through a slit onto the film giving a variable-width slit exposure onto the film.

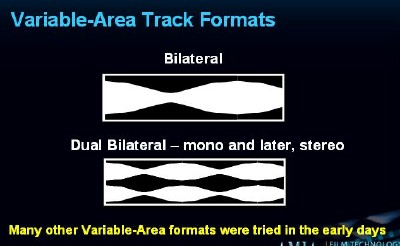

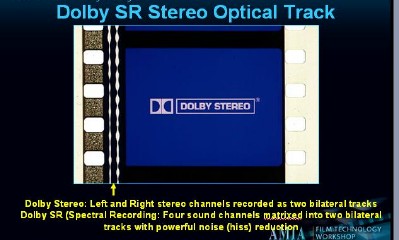

Variable area tracks can be (single) bilateral, as used in 16mm prints, or dual-bilateral, as used in 35mm prints.

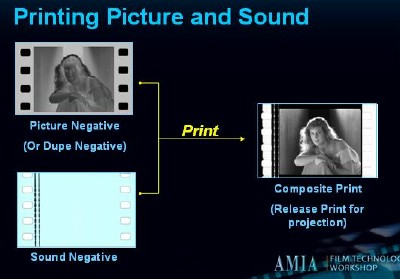

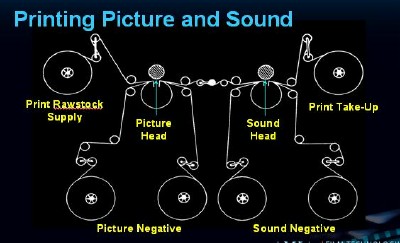

After sound recording and mixing have produced a sound negative film, and the picture has been edited and special effects added, the two negatives are printed onto a single print film to give the Release Print.

The two negatives are printed together using separate heads for Picture and Sound, taking care to start using precise sync marks.

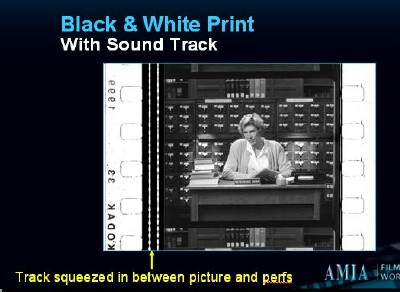

The sound track is printed in a narrow area between the picture and the film perforations, with the sound leading the picture by 21 frames.

Just a reminder that when the film is projected, the sound is reproduced from a photo-electric sound head below the picture, with the film carefully threaded up to give the required exact 21 frame separation.

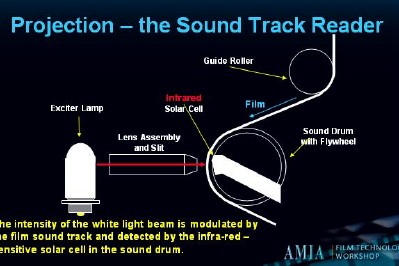

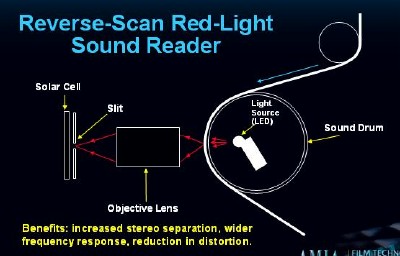

The sound head consists of a lamp focussed through a horizontal slit onto the sound track and the transmitted light, modulated by the sound track, falling onto a photo-cell (or “solar cell” in old parlance). These cells were originally of infrared (IR) sensitivity whose wavelengths were well modulated by the silver image of the track on the film.

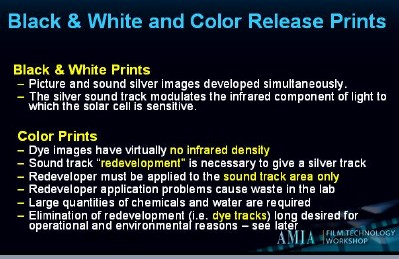

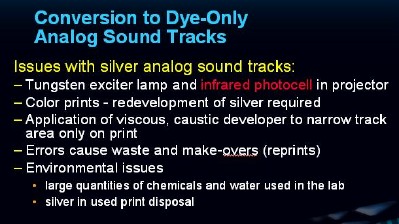

This arrangement worked perfectly for the silver image of the track on black and white film but when color arrived it was found that the dye images had almost no IR density and could only produce a very faint reproduction of the sound track. The answer to this problem should have been to change all the projector photocells to visible-sensitive cells but this was considered too much of an imposition on all the cinemas worldwide. In order to make the color Release Prints compatible with all the IR-sensitive projector sound heads, the sound track was “re-developed” to give a silver image as well as a dye image.

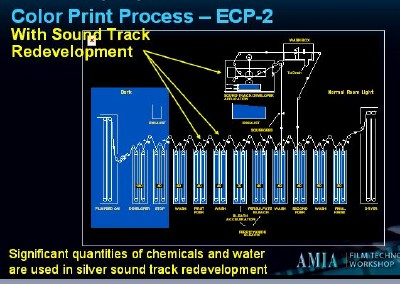

Sound track redevelpment required the application of as narrow bead of viscous black and white developer solution to the track area only, allowing it to work for a few seconds and then wash it off cleanly without contaminating the adjacent picture area. This added to the chemical and water requirements of the processing machine and quite often application errors required a print to be rejected, at further cost. The elimination of this redevelopment took many decades to be achieved finally about 2005 with dye-only tracks.

There were many reasons to convert to dye-only tracks and a Dye Tracks Committee worked from about 2000 to 2005 to achieve this.

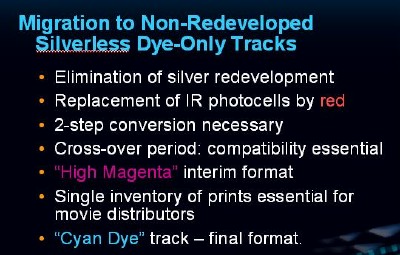

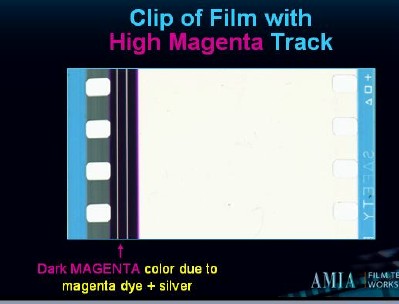

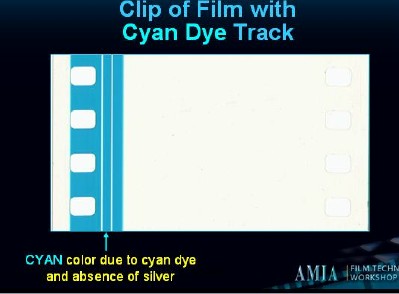

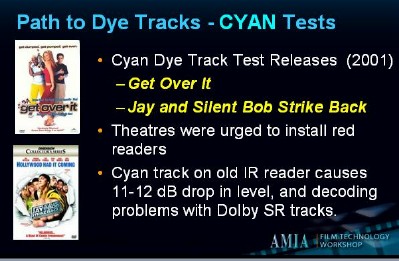

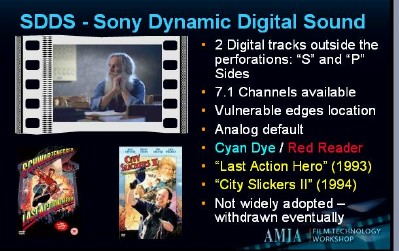

It was found that a 2-step conversion from redeveloped silver tracks to dye-only would be necessary to minimise complications in the laboratories, film distributors and the cinemas. An intermediate step, called the High Magenta track, was used temporarily for a short time before final conversion to the Cyan Dye track.

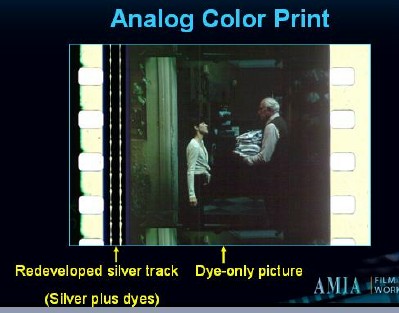

The appearance of a redeveloped silver track is dark blue, consisting of grey silver plus magenta and cyan dyes.

The High Magenta track was dark magenta, with only magenta dye in addition to the grey silver.

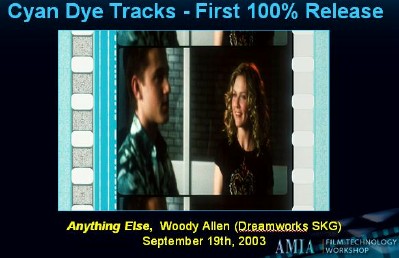

The final format, the Cyan Dye track consiste dof cyan dye only, with no silver.

With the need to change all the projector sound readers to play dye tracks, the opportunity was taken to convert the optical design to the better “reverse scan” format with a red LED light source inside the sound drum and the photocell outside the drum.

The first film test-released with the transition High Magenta format in a limited number of prints was City of Angels in 1998. There were no problems and full conversion followed shortly afterwards. This was publicised to the cinemas who were encouraged to convert to the Red Readers necessary for the final Cyan Dye format.

Once about 85% of projectors were converted to Red Readers the first test releases of Cyan Dte tracks were Get Over It and Jay & Silent Bob Strike Back in 2001.

The first 100% release weith the Cyan Dye track was Anything Else in 2003.

IN June 2006 all th emajor studios committed to conversion to Cyan Dye Tracks.

The Dye Track Committee which had coordinated the conversion from silver- to Dye Tracks was awarded a Scientific & Technical Award (technical Oscar) by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences in 2007.

Going back a little, let’s talk about stereo sound for motion pictures. The first (analog) format was Dolby SR in which 4 channels of stereo sound were encoded into the two halves of a dual bilateral track and decoded in the projector. Powerful noise (hiss) reduction, a major Dolby advance, was incorporated.

Whilst consumers had been enjoying digital sound since 1980 when the CD was introduced. it took another ten years before digital sound tracks came to cinemas, bringing many quality benefits.

Of the various formats proposed, three were used commercially – Dolby Digital SR*D. DTS and Sony SDDS.

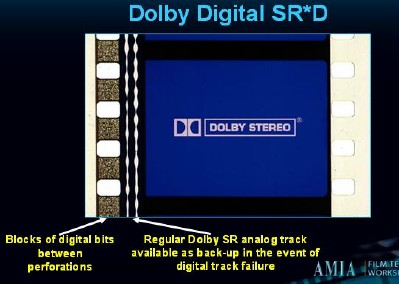

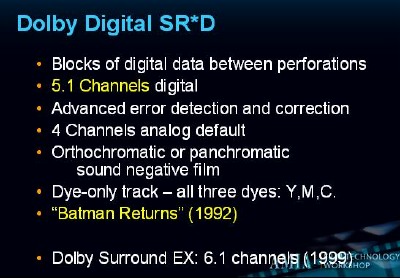

Dolby Digital SR*D tracks were placed in blocks between the perforations on the same side of the print as the analog track, which was retained to provide back-up in the event of a digital failure. In practice, such failures were very uncommon and the fears of the distributors were unfounded.

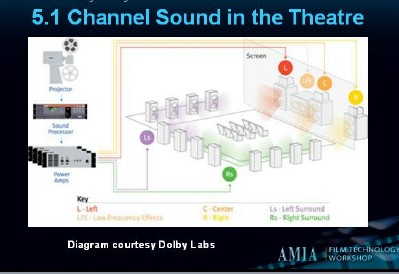

Dolby Digital SR*D boasted “5.1 channels” a sound engineer’s joke for five full-bandwidth channels plus one narrow-bandwidth “subwoofer ” channel.

Dolby Digital SR*D turned out to be the most successful of the three competing digital formats.

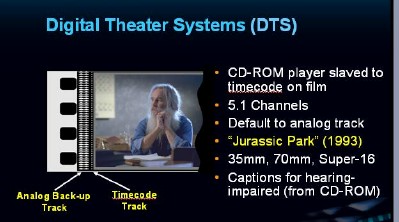

Digital Theatre Systems (DTS) adopted a quite different principle, harping back to the earliest sound-on-disc systems such the Vitaphone disc systemn used for The Jazz Singer in 1927. They used a separate CD disc to carry the sound, synchronized to a timecode track on the film. Among other things this allowed the use of different CDs for foreign-language versions.

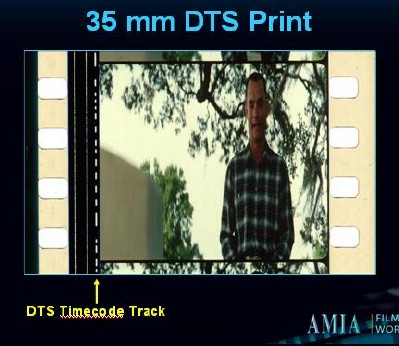

Location of the DTS timecode track between the picture and the back-up analog tracks.

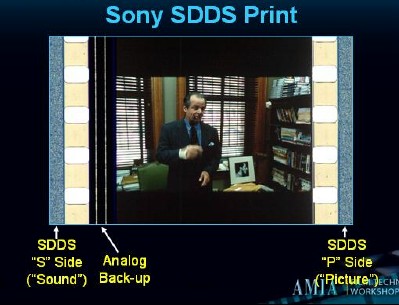

With so much of the “real-estate” on the film now occupied, Sony had to use the areas outside of the perforations on both sides of the film for their Sony Dynamic Digital Sound (SDDS) system, which boasted 7.1 channels of sound. This was used for Last Action Hero (1993) and City Slickers II (1994). It was the last digital format to be launched, after Dolby SR*D and DTS had established themselves. SDDS was not a commercial success and was withdrawn after a few years.

The SDDS tracks were located on the edges of the film, where it ran in physical contact with the rails in the projector gate and was thus very susceptible to scratching and failure, even with advance error correction. This further contributed to the demise of this format.

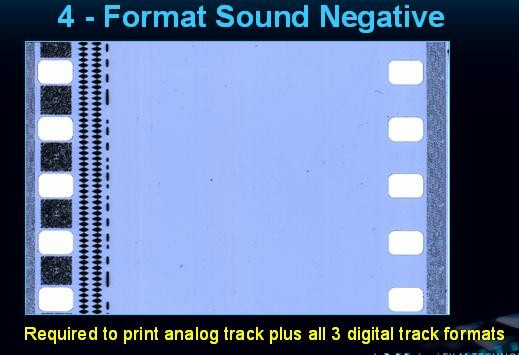

In order to print all three digital sound formats in a single pass through the printer in addition to the analog track, which was retained for safety back-up in the event of a digital failure, a special sound negative film was developed with all the required photographic cjaracteristics.

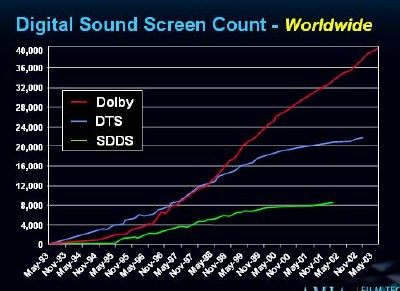

The history of the three digital formats was of Dolby SR*D taking the lead after an initial lead by DTS. Sony SDDS never achieved a high share and was eventually withdrawn.

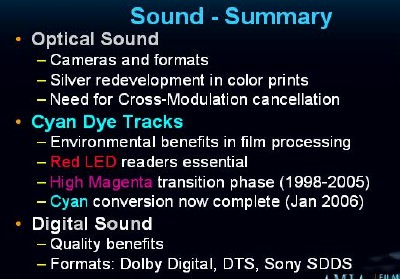

Summary.

Picture courtesy Warner Bros.